What is manufactory? Definition from history 7. The meaning of the word “manufactory”

The formation of modern civilization was a rather complex and lengthy process, which underwent various transformations as it developed. This is a long historical period - from about the 15th century. to the present time, and in some countries this period has not yet ended.

The modernization process, i.e. The transition from feudalism to capitalism goes through various phases of development: early industrial (XIV-XV centuries), middle industrial (XVI-XVIII centuries), late industrial (XIX centuries) and post-industrial (XX centuries).

At the early industrial stage of development of the bourgeoisie, a long-term gradual formation of new social institutions and elements of the bourgeois formation takes place, initial capital is accumulated, and manufactories (hand-made production) appear - the first signs of capitalism.

Cities were the center of development of bourgeois relations. A new layer of people (the third estate) was emerging there, consisting mainly of merchants, moneylenders and guild foremen. All of them had capital, the shortest way to acquiring which was through trade and usury operations. These capitals were not hidden in chests, but were invested in production. Moreover, into a new type of production, more efficient, giving high profits.

During this era, manufacturing began to replace the craft workshop. Manufacture is a large capitalist enterprise, based, in contrast to the workshop, on the internal division of labor and hired force. Manufactories were serviced with the help of hired labor; it was headed by an entrepreneur who owned capital and the means of production. Manufactures, the primary forms of capitalist enterprise, appeared already in the 14th-15th centuries.

There were two forms of manufacture: centralized (a merchant or entrepreneur himself created a workshop, a shipyard or a mine, and acquired raw materials, materials, equipment himself) and much more widespread - dispersed manufacture (the entrepreneur distributed raw materials to home-based artisans and received from them finished goods or semi-finished products).

The emergence of manufacture meant a significant increase in the productive forces of society. Its technical basis was still the use of the same tools as in handicraft production.

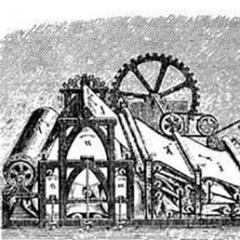

Later, manufactories began to use technical devices that were more or less complex for those times to use water and wind energy. Shafts, gears, gears, millstones, etc., driven by a water-filled wheel, were used in flour-grinding and grain milling, for making paper, in sawmilling, in the production of gunpowder, for drawing wire, cutting iron, driving a hammer, etc.

In the manufacturing era, profound changes occur in the economic life of society, a catastrophic breakdown of the old economic way of life, the old picture of the world.

The main advantage of manufactory was that it was a large-scale production and created opportunities for narrow specialization of labor operations as a result of the technical division of labor. This helped to increase the output of hired workers several times compared to a craft workshop, where all operations were performed primarily by one master.

But until machines were invented, capitalist production was doomed to remain only a structure in the feudal economic system.

Farms.

The countryside, the main stronghold of feudalism, was drawn into bourgeois relations much more slowly than the city. Farms were formed there, with hired labor from peasants who had lost their land as a result of transformations, i.e. who ceased to be peasants in the full sense of the word. This process of de-peasantization went through various intermediate forms, as a rule, through the transition to rent, which meant the abolition of fixed payments and rights to hereditary holding of land.

In the village, rich peasants, merchants, or sometimes the feudal lords themselves could act as entrepreneurs. This happened, for example, in England, where there was a process of so-called enclosures, i.e. the forced removal of peasants from the land in order to turn it into pasture for sheep, the wool of which was sold.

The rate of development of capitalism depended on the speed of penetration of bourgeois relations into the countryside, which was much more conservative than the city, but produced the bulk of production. This process proceeded most rapidly in England and the Northern Netherlands, where the rapid flourishing of manufacturing coincided with the bourgeoisification of the countryside.

In England and Holland in the XVI-XVII centuries. an intensive bourgeois restructuring of agriculture took place; large capitalist leases were approved while preserving the noble land ownership of landlords (landowners). These countries have already seen the introduction into practice of new types of agricultural tools (light plow, harrow, seeder, thresher, etc.).

The bourgeois progress of agriculture provided raw materials and an influx of labor into industry, because peasants, left without land and unable to find work in the village, went to the city.

The development of capitalism was accompanied by technical progress, the destruction of traditional corporate ties, and the formation of common markets - national and pan-European.

In this era, a new “hero of the time” appeared, an enterprising, energetic person who was able to withstand competition and create capital literally out of nothing.

But in the XVI-XVII centuries. Even in those countries where bourgeois relations successfully developed, the new way of life still existed in the “context” of feudal relations, which were still quite strong and did not want to voluntarily give up their place.

The base of capitalism was quite weak, so there was room for movement back, which is what happened in a number of European countries. These included Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Germany.

Large enterprises that used manual labor are called manufactories by historians. This form of production served as a transition from communal agriculture to industrial capitalism. The first manufactories appeared in Europe at the end of the 14th century, as in the most developed part of the world at that time.

The active growth of industrial production was facilitated by the development of urban handicrafts. Craftsmen united in workshops on a territorial and industrial basis, distributing labor costs among themselves and using the division of labor. The emergence of manufactories was also facilitated by agricultural successes. Peasants created significant surplus value and also needed products from the processing of primary materials, so weaving and rope manufactories were among the first to appear. With the increase in the profitability of production, the experience of the first industrialists was picked up by other artisans, organizing metallurgical, mining, printing and other types of manufactories.

Only rich merchants or talented artisans who managed to unite like-minded people around them could own their own production. Often states themselves created certain types of manufactories.

In Russia, the beginning of the period of industrial production is considered to be the 17th century. The numerous trials that befell our country during the Time of Troubles hampered the progress and development of industry in every possible way, but the first manufactories, whose influence on the development of the state can still be felt, appeared precisely then.

The main difference between domestic manufactories and their European counterparts was the use of unfree labor. While production abroad employed mainly professional craftsmen and free townspeople, in Russia the owners of manufactories hired serfs who were assigned to a specific place and did not have the right to voluntarily leave it. Of course, both the quality of domestic products and the pace of emergence of the manufactories themselves suffered from this, since few people had sufficient capital or personal freedom to earn it.

The Moscow Cannon Yard was the very first Russian manufactory. As statehood strengthened after the Time of Troubles and intervention, the state increasingly invested in the development of industry. Production began to appear in Tula, Arkhangelsk and the Urals. For many years, Ural manufactories (and later factories) became pillars of development and support for Russia. First of all, the authorities were interested in weapons production, and government money was directed to the creation and support of such enterprises; related industries, metallurgy and mining, concentrated precisely in the Urals, developed accordingly.

In the production process, not only primitive human-powered mechanisms were used, but also water-powered mechanisms: blacksmith bellows and blacksmith hammers. Foreigners were allowed to build their own manufactories in Russia, which primarily served the royal court and boyars. The existence of foreign industries allowed domestic industrialists to adopt foreign experience and new technologies. The largest number of foreigners (mainly Dutch and Danes) owned manufactories in the Tula province, which at that time was the largest industrial center in Russia.

Peter I gave the greatest impetus to the development of manufactories. During his reign, at least 200 new industries were opened in addition to those already existing at that time. Qualified specialists and scientists were actively recruited from abroad, and the “sovereign’s people” regularly went to Europe to improve their skills. At the same time, all manufactories remained semi-feudal enterprises, which significantly reduced their productivity. Peasants were simply assigned to specific production without specifying a deadline. Thus, state peasants actually found themselves in the hands of industrialists, and they, in turn, had virtually no responsibility for them. These peasants were called possessions.

It is customary to distinguish three main types of manufactories in Russia: state-owned (state), landowners and merchants. They differed from each other not only in the form of ownership, but also in the nature of the labor force involved. Landowner manufactories were the most conservative and least profitable. Basically, they covered the needs of the county for any products: fabric, dishes, cutlery, paper, etc. There have never been hired workers in such factories.

State-owned manufactories enjoyed unlimited administrative resources and labor. The authorities could invest funds from the budget in any type of production that seemed profitable, buy out (and sometimes take by force) private factories. It was in state-owned manufactories that foreign specialists were actively involved. Also, many future industrialists and factory owners began their history as peasants who worked in the sovereign's factory, then bought their freedom and applied the accumulated knowledge in their own production.

Merchant manufactories were the basis of Russian industry. Thanks to the mixed use of serf and hired labor, they achieved a high level of productivity, often not inferior to European manufactories. It was the Russian private industry that became famous throughout the world and was able to compete on equal terms in the European market. Merchant-industrialists often turned to the tsar for help and generally tried not to deviate from state interests.

The Sveteshnikovs, Stroganovs, Demidovs, Shustovs (who emerged from peasants as nobles) and many other industrialists created a new elite of the Russian state. They laid the foundations of capitalism and were the first to notice the prerequisites for the industrial revolution, which later allowed the Russian Empire to become one of the most powerful states.

Chapter 1. The emergence of manufactories

Manufacture (from the Latin manus - hand and factura - production) is a form of capitalist industrial production and a stage in its historical development that precedes large-scale machine industry. It is a production based on manual labor. But manufacture differs from simple cooperation in that it is based on the division of labor. Subsistence farming in its pure form did not exist even during the time of early feudalism, not to mention the 17th century. The peasant, like the landowner, turned to the market to purchase products, the production of which could be organized only where the necessary raw materials, such as salt and iron, existed.

In the 17th century, as in the previous century, some types of crafts were widespread. Everywhere, peasants wove linen, tanned leather and sheepskin for their needs, and provided themselves with residential and outbuildings. What made the development of small industry special was not home crafts, but the spread of crafts, i.e. manufacturing of products to order and especially small-scale commodity production, i.e. manufacturing products for the market.

The most important innovation in industry in the 17th century. was associated with the emergence of manufacture. It has three characteristics. This is primarily a large-scale production; Manufacture, in addition, is characterized by division of labor and manual labor. Large-scale enterprises that used manual labor, in which the division of labor was in its infancy, are called simple cooperation. If hired labor was used in cooperation, then it is called simple capitalist cooperation.

The type of simple capitalist cooperation included artels of barge haulers that pulled plows from Astrakhan to Nizhny Novgorod or the upper reaches of the Volga, as well as artels that built brick buildings. The most striking example of organizing production on the principle of simple capitalist cooperation (with the indispensable condition that labor was hired) was salt production. The trades of some owners reached enormous proportions: at the end of the century, the Stroganovs had 162 breweries, the guests Shustov and Filatov had 44 breweries, and the Pyskorsky Monastery had 25 Klyuchevsky V.O. A complete course of lectures on Russian history. M., 2013. But in the salt mines there was no manufacturing division of labor: only the salt maker and the salt maker participated in the salt production. All other workers (wood hauler, stove maker, blacksmith, well driller from which brine was extracted) did not participate in the production of salt. However, some historians classify salt-making industries as manufactories.

The first manufactories arose in metallurgy; water-powered factories were built in places where there were three conditions for this: ore, forest and a small river, which could be blocked with a dam in order to use the energy of water in production. Manufacturing production began in the Tula-Kashira region - the Dutch merchant Andrei Vinius launched a water-powered plant in 1636.

Let us note the most characteristic features of the emergence of manufacturing production in Russia. The first of them is that large enterprises arose not on the basis of the development of small-scale commodity production into manufacture, but by transferring ready-made forms to Russia from the countries of Western Europe, where manufacture already had a centuries-old history of existence. The second feature was that the initiator of the creation of manufactories was the state. To attract foreign merchants to invest capital in production, the state provided them with a number of significant privileges: the founder of the plant received a cash loan for 10 years.

In turn, the factory owner obliged to cast cannons and cannonballs for the needs of the state; Products (pans, nails) entered the domestic market only after the state order was completed.

Following the Tula-Kashira region, the ore deposits of the Olonetsky and Lipetsk regions were brought into industrial exploitation. Water-processing plants were founded by such large landowners as I.D. to satisfy the iron needs of their estates. Miloslavsky and B.I. Morozov. At the end of the century, the merchants Demidov and Aristov joined manufacturing production. Metallurgy was the only industry in which, until the 90s. manufactories operated.

In the 17th century Russia has entered a new period in its history. In the field of socio-economic development, it was accompanied by the beginning of the formation of an all-Russian market.

In its emergence and development, the decisive role was not in manufactories, which covered only one branch of industry and produced an insignificant share of marketable products, but in small-scale commodity production. Interregional connections cemented fairs of all-Russian significance, such as Makaryevskaya near Nizhny Novgorod, where goods from the Volga basin were transported, Svenskaya near Bryansk, which was the main point of exchange between Ukraine and the central regions of Russia, Irbitskaya in the Urals, where the purchase and sale of Siberian furs and industrial goods of Russian and foreign origin intended for the population of Siberia.

The largest trading center was Moscow - the center of all agricultural and industrial goods, from grain and livestock to furs, from peasant handicrafts (linen and homespun cloth) to a diverse assortment of imported goods from the countries of East and Western Europe.

The upper layer of merchants consisted of guests and trading people of the living room and cloth hundreds. Guests are the richest and most privileged part of the merchant class. They were given the right to freely travel abroad on trade matters, the right to own estates, they were exempt from billeting, taxes and some townsman services. Traders of the living room and cloth hundreds had the same privileges as guests, with the exception of the right to travel abroad.

For the privileges granted, members of corporations paid the state by fulfilling a number of onerous tasks that distracted them from trading their own goods - they were trade and financial agents of the government: they purchased goods whose trade was in a state monopoly, managed the customs offices of the country's largest shopping centers, acted as appraisers of furs and etc. The state monopoly on the export of a number of goods (furs, black caviar, potash, etc.), which were in demand among foreign merchants, significantly limited the opportunities for the accumulation of capital by the Russian merchants.

Sea trade with the countries of Western Europe was carried out through a single port - Arkhangelsk, which accounted for 3/4 of the country's trade turnover. Over the course of the century, the importance of Arkhangelsk, although slowly, increased: in 1604, 24 ships arrived there, and at the end of the century - 70.

The main consumers of imported goods were the treasury (weapons, cloth for uniforms of servicemen, etc.) and the royal court, which purchased luxury goods and manufactured goods. Trade with Asian countries was carried out through Astrakhan, a city with a diverse national composition, where, along with Russian merchants, Armenians, Iranians, Bukharans, and Indians traded, delivering silk and paper materials, scarves, sashes, carpets, dried fruits, etc. The main product here was silk. -raw material in transit to Western European countries.

Western European goods were also delivered to Russia by land, through Novgorod, Pskov, and Smolensk. Here trading partners were Sweden, Lubeck, and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The peculiarity of Russian-Swedish trade was the active participation of Russian merchants in it, who did without intermediaries and delivered hemp directly to Sweden. However, the share of overland trade was small. The structure of foreign trade turnover reflected the level of economic development of the country: industrial products predominated in imports from Western European countries; agricultural raw materials and semi-finished products predominated in Russian exports: hemp, linen, furs, leather, lard, potash, etc.

Russia's foreign trade was almost entirely in the hands of foreign merchants. Russian merchants, poorly organized and less wealthy than their Western European counterparts, could not compete with them either in Russia or in the markets of those countries where Russian goods were imported. In addition, Russian merchants did not have merchant ships.

The dominance of foreign trading capital in the domestic market of Russia caused acute discontent among Russian merchants, which manifested itself in petitions submitted to the government demanding the expulsion of foreign merchants (English, Dutch, Hamburgers, etc.) from the domestic market. This demand was first made in a petition in 1627 and was then repeated in 1635 and 1637. At the Zemsky Sobor 1648 - 1649. Russian merchants again demanded the expulsion of foreign merchants.

The persistent harassment of Russian merchants was only partially crowned with success: in 1649 the government deprived only the English of the right to trade within Russia, and the basis was the accusation that they “killed their sovereign, King Charles, to death.”

Trade people continued to put pressure on the government, and in response to the petition of the eminent man Stroganov, on October 25, 1653, it promulgated the Trade Charter. Its main significance was that instead of many trade duties (appearance, driving, pavement, skid, etc.) it established a single duty of 5% on the price of the goods sold. The trade charter, in addition, increased the amount of duty from foreign merchants instead of 5%, they paid 6%, and when sending goods inside the country, an additional 2% Polyansky F.Ya., Economic structure of manufactory in Russia in the 18th century, M., 2006. The trade charter, therefore, was of a patronizing nature and contributed to the development of internal exchange.

Even more protectionist was the New Trade Charter of 1667, which set out in detail the rules of trade for Russian and foreign merchants. The new charter created favorable conditions for Russian trading people to trade within the country: a foreigner selling goods in Arkhangelsk paid the usual 5% duty, but if he wanted to take the goods to any other city, then the size of the duty was doubled, and he was only allowed to conduct wholesale trade. It was forbidden for a foreigner to trade foreign goods with a foreigner.

The New Trade Charter protected Russian merchants from the competition of foreign merchants and at the same time increased the amount of revenue to the treasury from collecting duties from foreign merchants. The drafter of the New Trade Charter was Afanasy Lavrentievich Ordyn-Nashchokin. This representative of a seedy noble family became the most prominent statesman of the 17th century. He advocated the need to encourage the development of domestic trade, the liberation of the merchants from the petty tutelage of government agencies, and the issuance of loans to merchant associations so that they could withstand the onslaught of wealthy foreigners. Nashchokin did not consider it shameful to borrow something useful from the peoples of Western Europe: “a good person is not ashamed to learn from the outside, from strangers, even from his enemies.”

Thus, the prerequisites for the formation of manufacture were: the growth of crafts, commodity production, the emergence of workshops with hired workers, the accumulation of monetary wealth as a result of the initial accumulation of capital. Manufacture arose in two ways:

1) the unification in one workshop of artisans of various specialties, due to which the product was produced in one place until its final manufacture.

2) the unification in a common workshop of artisans in the same specialty, each of whom continuously performed the same separate operation.

State and subjects in the Arab Caliphate

The emergence of new social relations gave rise to a new ideology in the form of a new religion - Islam. Islam (literally “submission”), or otherwise Islam, was formed from the combination of elements of Judaism, Christianity...

Dissident movement in the USSR

At the end of the 50s. In the Soviet Union, the beginnings of a phenomenon emerged that would turn into dissidence a few years later. Dissidents were those representatives of society who openly...

Ancient Rome

Greco-Roman legend tells about the founding of Rome as follows. During the destruction of Rome, Troy, very few survived, including Aeneas, the son of Anchises and Aphrodite...

Ancient Chinese civilization Shan (Yin)

In the second half of the 2nd millennium BC...

We know little about the origins of the order. It is traditionally believed that the first and foremost in the order were such individuals as Hugh de Payen and Geoffroy de Saint-Omer. We know very little about the personality of Hugh de Payns, except that he was no longer young...

Spiritual knightly orders of the Crusaders in the East

The early period of the order is barely reconstructed from the semi-legendary news of medieval chroniclers. Usually historians refer to the meager report of Archbishop Guillaume of Tire about a certain holy man Gerard, who allegedly founded the order around 1070...

History of Kuzbass cities

The history of the city is inextricably linked with the history of the annexation and development of Siberia by the Russian state. In 1618, a detachment of Russian servicemen on the banks of the river. Tom "at the mouth of the Kondoma" a new fort was erected, which received the name Kuznetsky...

Manufacturing and industrial production in Russia

Large trading and merchant capital was the main source of the creation of the first manufactories of Peter the Great's time. Among Peter’s “manufacturers” the names of former Moscow “guests” and merchants were replete with names...

Manufacturing production in Belarus

manufacturing patrimonial capitalist industry The creation of the manufacturing industry on the territory of Belarus was started by the Belarusian-Polish princes Radziwills...

Paris Commune

The rise of the Paris Commune was preceded by the uprising of March 18, 1871. The pretext for it was an attempt by government troops to take away artillery from the National Guard. Late in the evening of March 17, 1871...

Polis in ancient Greek civilization

In the culture of Ancient Greece, there is a combination of traditional features dating back to the archaic and even earlier eras, and completely different ones, generated by new phenomena in the socio-economic and political spheres...

Prerequisites and features of Russian multi-party system at the beginning of the twentieth century

The formation of the party system was greatly influenced by: firstly, significant differences (compared to Western Europe) associated with the social structure of society; secondly, the uniqueness of political power (autocracy); thirdly...

Entrepreneurship in medieval Rus'

The strengthening of Moscow, which stood at the key point of Russian trade, where the river routes connecting the basins of the Volga, Oka, and other smaller rivers passed, was largely due to the zealous, practical policy of the Moscow princes...

Spartan polis

Sparta, or Lacedaemon, is an ancient Greek polis, city-state, which arose in the 9th century BC. Sparta was an example of a slave-owning aristocracy. The most Doric of all the states of Ancient Greece...

Medieval education

Among the total mass of medieval universities, the so-called “mother” universities stand out. These are the universities of Bologna, Paris, Oxford and Salamanca. According to some researchers...

Manufactory(Latin.manufactura, manus-hand and factura-processing, manufacturing) - a form of industrial production characterized by the division of labor between hired workers and the use of manual labor. Manufacture preceded plants and factories.

Prerequisites for the formation of manufactory

- growth of crafts, commodity production

- the emergence of workshops with hired workers

- accumulation of monetary wealth as a result of primitive capital accumulation

The origins of manufacture

- the unification of artisans of various specialties in one workshop, due to which the product remained in production in one place until its final production

- a union of artisans of the same specialty in a common workshop, each of whom continuously performed the same operation.

Forms of manufacture

Scattered manufactory

In scattered manufacturing, the entrepreneur bought up and the small manufacturer was actually in the position of a hired worker who received wages, but continued to work in his home workshop.

Mixed manufacture

Mixed manufacturing combined the execution of individual operations in a centralized workshop with work at home. Such manufacture arose, as a rule, on the basis of home handicrafts.

Centralized manufactory

The most developed form was centralized manufactory, which united hired workers in one workshop. Manufacture led to the specialization of workers and the division of labor between them, which increased its productivity.

Manufactory in Russia under Peter I

Types of manufacture (state-owned, patrimonial, possessional, merchant, peasant)

In industry there was a sharp reorientation from small peasant and handicraft farms to manufactories. Under Peter, at least 200 new manufactories were founded, and he encouraged their creation in every possible way.

Russian manufactory, although it had capitalist features, but the use of predominantly peasant labor - sessional, assigned, quit-rent, etc. - made it a serf enterprise. Depending on whose property they were, manufactories were divided into state-owned, merchant and landowner-owned. In 1721, industrialists were given the right to buy peasants to assign them to the enterprise (possession peasants).

State-owned factories used the labor of state peasants, assigned peasants, recruits and free hired craftsmen. They served heavy industry - metallurgy, shipyards, mines.

The merchant manufactories, which produced mainly consumer goods, employed both sessional and quitrent peasants, as well as civilian labor. Landowner enterprises were fully supported by the serfs of the landowner-owner.

History of manufacturing production in the leading countries of Western Europe

The history of the genesis of the industrial countries of Western Europe is closely connected with the development of manufacturing in the 16th-18th centuries, on which the economic development of the countries as a whole largely depended. A characteristic feature of manufacturing compared to the previous simple cooperation was the transition to an operational division of labor in the manufacture of goods, which led to a significant increase in labor productivity. Manufacturing production historically prepared the preconditions for large-scale machine industry.

In its classical form, the process of initial accumulation of capital took place in England. Back in the XII-XIV centuries. England exported raw wool for processing abroad, in particular to Holland. In the 15th century In England, manufactories began to be built for the production of cloth from their own raw materials, the demand for which increased every year. In the 16th century About half of the working population of England was engaged in the production of woolen fabrics, and at the beginning of the 17th century. 90% of English exports were cloth products.

The second aspect of primitive capital accumulation was the accumulation of significant amounts of money in the hands of individuals. Here, England was characterized by such sources as: the use of public debts and high interest rates on them, the implementation of a policy of protectionism (patronage), which enabled the state to set high customs tariffs that protected its own manufacturer from competition.

A significant role for England in the accumulation of capital was played by the Great Geographical Discoveries, the robbery of the colonies, especially India, unequal trade, piracy, and the slave trade, which acquired large proportions in the 17th century, when thousands of blacks from Africa were exported for sale to America. The process of capital accumulation was also positively influenced by a political factor - the bourgeois revolution (1640-1660), which brought the bourgeoisie to political power.

The above sources provided an opportunity for individuals in England to accumulate large funds, which were invested in the development of manufacturing production and turned into capital.

As for Holland, the process of initial capital accumulation began earlier than in England. Back at the end of the 14th century. in Holland there was a destruction of feudal relations in the countryside and the formation of farms, and as a result, the emergence of a large number of free labor.

Bourgeois revolution in Holland in the second half of the 16th century. accelerated the process of initial capital accumulation, which occurred through such sources as: the development of financial transactions; agriculture; robbery of colonies and unequal exchange of goods with them of trade income. The transformation of Holland into a leading financial power in the world actively influenced the development of manufacturing production based on the use of civilian labor. Consequently, the opportunity arose to quickly develop shipbuilding, cloth, linen, silk and other manufactories, create enterprises for processing agricultural products, and turn the country into the largest trading and financial power in the world.

The influence of the Great Geographical Discoveries accelerated the process of initial accumulation of capital in England, Holland and other countries of Western Europe and the destruction of the natural feudal economy; These discoveries drew the feudal economy into market relations and had a positive effect on the expansion of manufacturing production, which created the preconditions for the transition to an industrial society.

From the middle of the 17th century. manufacture becomes the dominant form of production, covering an ever-increasing amount of output of various types of goods and deepening the international division of labor. The sectoral composition of manufactories was largely determined by natural-geographical conditions and the historical development of a particular country. Thus, in England, cloth, metallurgical, metalworking and shipbuilding manufactories mainly predominated; in Germany - mining, metalworking and construction, in Holland - textile and shipbuilding.

The development of manufacturing production caused a deterioration in working conditions for workers, an increase in the length of the working day, the use of female and child labor, and a decrease in real wages, which contributed to the aggravation of social contradictions.

The first bourgeois revolutions in Western Europe and the USA made a significant contribution to the development of manufacturing production: in the Netherlands (1566-1609), England (1640-1649), France (1789-1794), USA (1775-1783). These revolutions created the conditions for the bourgeoisie to come to political power, which adopted laws aimed at the further development of manufacturing production, the expansion of trade, finance, and the elimination of feudal remnants that hampered the economic development of the country. The main result of bourgeois revolutions is the final victory over feudalism and the establishment of a bourgeois-democratic system. The main direction of activity of the bourgeoisie, which came to political power, was to create favorable conditions for the development of manufactures and direct all laws in the financial sphere to accumulate money in various ways and protect the country's domestic market from foreign goods.

The bourgeois revolution in England had a significant influence on the development of manufacturing and trade. It had universal historical significance, signaling the final liquidation of feudalism. Having come to political power during the revolution, the English bourgeoisie adopted laws aimed at developing industry and trade, strengthening finances. So, in 1651, the “Navigation Act” was adopted, according to which all goods that were imported into England were to be transported only on English ships; Parliament, with its laws, supported the process of fencing, which provided cheap labor for manufactories. The government actively pursued a policy of capital accumulation in the country, which strengthened the monetary system and production. To strengthen the credit system, the Bank of England was opened in 1694, and the territory of the colonies expanded significantly. In the 18th century England became the largest colonial power in the world, which had a positive impact on the industrial development of the country and provided a market for its goods.

The economic policy of the French bourgeois revolution was actively anti-feudal. The revolution abolished the tax privileges of the nobles, eliminated the regulation of production and workshops, proclaimed freedom of trade, introduced a policy of protectionism, and largely resolved the agrarian issue by allocating peasants with a small amount of land. In January 1800, the French Bank was created in the country, and the credit and financial system developed.

Development of trade in the XVII-XVIII centuries. in countries such as Holland, England and France leads to the fact that trade, especially colonial trade, becomes one of the leading sectors of the economy, bringing huge profits to the countries. Therefore, the policy of trade balance and expansion of trade relations between countries is of great importance. The trade balance was calculated as the difference between exports and imports of goods.

Consequently, already at the beginning of the development of world trade, countries believed that they needed to export more goods abroad than import them in order to have a positive balance, which actively influenced the accumulation of money in the country.

To ensure a positive trade balance, Western European countries actively pursued a policy of protectionism aimed at protecting industry and the domestic market of countries from the penetration of foreign goods by laws and regulations. For this purpose, primarily high duty rates on the import of goods from abroad were used. At the same time, protectionist policies encouraged the development of the national economy and protected it from foreign competition. The policy of protectionism, for example, was actively pursued by England, and this had a positive effect on the development of manufacturing production.

Thus, during the manufacturing period of economic development in the countries of Western Europe, under the influence of the Great Geographical Discoveries, the rapid initial accumulation of capital, the creation of the colonial system and the emergence of the world market, the natural feudal economy decomposed. Along with this, market relations developed; Internal and foreign trade is acquiring significant volumes, which contributes to the expansion of manufacturing production, which laid the foundations for the transition to an industrial society.

from lat. manus - hand and factura - production), an enterprise based on the division of labor and manual craft techniques. Existed in the 16th-18th centuries. in Western European countries, from the 2nd half of the 17th century. until the middle of the 19th century. in Russia. Prepared the transition to machine production.

Excellent definition

Incomplete definition ↓

MANUFACTURE

late lat. manufactura - handmade, from lat. manus - hand and facio - I do, I make) - one of the early forms of capitalism. organization of industry, in which the craft is preserved. technology, but production is based on cooperation and technology. division of labor in the department capitalist enterprises, among workers employed and exploited by one individual capital. M. immediately preceded the factory. In the 16th-18th centuries. the term "M." meant, as a rule, not a form of industrial. organizations, and the manufacturing industry in general. The concept of M. as a definition. historical-economics phenomenon, as well as the term itself in its specific meaning, were introduced into science by K. Marx. M. meant means. a step forward in the development of labor productivity, in the concentration of the means of production by capital. Compared to on their own. craft and simple capitalistic. cooperation, labor productivity in Moscow increased thanks to the systematic division of labor: “On the basis of manual production, there could be no other progress in technology except in the form of division of labor” (Lenin V.I., Soch., vol. 3, p. 375 ). The division of labor ensured increased productivity due to: 1) masterly specialization of “partial” workers (who constantly performed the same type of simple operations); 2) the resulting increase in labor intensity; 3) differentiation and increase in working tools, which in turn prepared the transition to machine technology. The division of labor in Moscow was created either by uniting artisans engaged in various crafts, or by uniting artisans performing the same or homogeneous work, with the subsequent division of labor between them. According to its internal technological structure M. was divided into heterogeneous, in which the finished product was obtained as a result of mechanical. combinations of independent partial products (for example, watch M.), and organic M., in which the product was produced through a sequential series of interconnected processes (for example, M. needles). Often M. combined both of these forms (combined M.). Historically, M. was prepared by societies. division of labor, development of small-scale production, differentiation of crafts, which began the process of the so-called. initial accumulation. Early forms of capital—lending and usury and especially trading—played an important role in capitalism, as well as in the genesis of capitalism in general. Marx distinguishes the following paths of transition to capitalism. relations in the industry, including, therefore, to M. One way was that the merchant directly subordinated the production of small-scale producers to himself. This path “... does not in itself lead to a revolution in the old mode of production, which is rather preserved and maintained as a necessary precondition for it” (Capital, vol. 3, 1955, p. 346). Another path was truly revolutionary - the transformation of the manufacturer-industrialist himself into a merchant and capitalist. In the history In reality, M. existed in the forms of scattered, mixed and centralized. In dissipated M., the entrepreneur-owner of capital (initially, most often a merchant-buyer) was engaged in the purchase and sale of the product of independent artisans, and then in supplying them with raw materials and tools of production. Having cut off the small producer from the market for finished products and from the market for raw materials, he gradually subordinated independent production to himself. artisans, reduced them to the position of hired workers who received wages, but continued, however, to work in their home workshops. In such a case, the buyer's trading capital passed into industrial capital. In the future, the exploitation of hired homeworkers engaged in various industries. operations and united by the same capital, created on one field of labor dispersed in space, but actually a single industry. Hand mechanism individual capital. However, most often the entrepreneur singled out certain detailed operations (often these were the final operations for the manufacture of a given type of product) and concentrated their execution in his workshop. That. A mixed-type workshop was created, combining a centralized workshop with the exploitation of domestic workers in the surrounding area. Such M. were very common and arose, as a rule, on the basis of home handicrafts in villages, as well as in cities, more quickly - on the basis of non-guild crafts, more slowly - as a result of the decomposition of the mountains. shop organization. Due to its prevalence in Moscow in the 16th-18th centuries. capitalist work from home burzh. Historians and economists call the domination. the form of industry of this era was limited to the “home system”, “commission system”, “distribution system”, etc., without making a distinction between any form of work at home and labor. Economically, the most developed was centralized labor, the region united hired workers (expropriated village artisans, bankrupt artisans in cities, impoverished guild masters, etc.) under one roof. Centralized policies were often imposed by government policies of absolutism. In the bourgeoisie Literally, the identification of centralized M. is very common. with the factory. The workers of M. have not yet formed into a special class. Their composition was characterized by extreme heterogeneity (various degrees of dependence on capital, different working conditions in centralized and dispersed capital, etc.). Manufacturing workers were most often separated in production, being scattered across departments. workshop; sometimes they still retained a connection with the property (workshop, land plot, etc.). M. developed a hierarchy of workers, which corresponded to the wage scale, and for the first time created a category of untrained workers. M. on a large scale accustomed workers to the discipline of hired labor, ugly cultivated in them only one-sided dexterity (“partial”, “detailed” workers), and artificially suppressed creativity. inclinations, production talents and abilities. However, capital at this early stage was not able to completely subjugate the wage worker, as happens in factory production; the exploitation of women and children, although widespread, was still insignificant compared to the factory; the institution of apprenticeship was preserved (albeit in a form modified compared to the guild one); Throughout the manufacturing period, entrepreneurs complained about the indiscipline of workers. Capital in an embryonic state “...provides its right to absorb a sufficient amount of surplus labor not only by the strength of economic relations, but also by the assistance of state power...” (ibid., vol. 1, 1955, p. 276). Hence the laws on lengthening the working day and force. establishment of wages during the period of manufacturing capitalism, published by the state. power. Elements of non-economic coercion was also sometimes expressed in coercion. attaching a worker to a certain capitalist (for example, workers of large privileged manufactories in France, Prussia). Early forms of M. are found sporadically in the 14th and 15th centuries. usually for sale. centers associated with large-scale production for export to foreign countries. market. Such are the markets in certain cities of Italy, Flanders, Brabant, etc. Bargaining, as a rule, played the leading role in them. and loan-lender. capital, and the subordination of labor to capital basically. was still of a formal nature. Early massacres were often still associated with the feudal-corporate guild system and were built on top of it. Dependent on the temporary favorable situation in foreign trade. market conditions, these early M. were not always a strong and stable economic phenomenon. life; behind the decline of external trade often followed the decline of their production. Outside of these large bargains. centers M. “...at first it settles not in cities, but in the countryside, in villages where there were no guilds...” (Marx K., Forms preceding capitalist production, 1940, pp. 48-49). These are, for example, wool weaving machines in the villages of Flanders in the 14th century. Early mills were also created in cities - in those industries where there were no guild corporations (for example, in Dutch cities in such new industries as flax, etc.). Crafts became the leading form of industry in economically advanced countries in the 16th–18th centuries, replacing the feudal-organized craft of the Middle Ages. workshops Some bourgeois. historians (E. Lipson, G. Hamilton, J. Nef, and others) exaggerate the degree of development of capitalism at its manufacturing stage, put forward the position of the coexistence of capitalism and the factory system in the 16th-18th centuries, and the emergence of factories even in the 14th century. , in particular in the industry of England. In England 16-18 centuries. the process of the origin and development of M. proceeded in the classical. forms and that is why Marx served as material for theoretical studies. generalizations. M. grew up here in an atmosphere of successful capitalist development. relations in all spheres of the economy and were themselves an indicator of the overall growth of capitalism. English M. were created on the basis of primarily internal. market. On the eve of English bourgeois revolutions of the 17th century M. have already spread widely throughout the country and were found even in economically backward counties of the North. They received primary importance in the leading industry of English. industry - in cloth, as well as in new industries (production of paper, glass, cotton and paper fabrics). In the cloth industry, centralized or mixed textiles were often created in the buildings of secularized monasteries. Such is Stump's workshop in Malmesbury, which employed up to 2 thousand workers, including homeworkers; the enterprise of the clothier Thacker from Bedford, which united approx. 500 workers. However, scattered M. were much more widespread, especially in economics. advanced districts text. prom-sti zap. and east counties (Reynold's manufactory around Colchester included about 500 homeworkers, Brewers in Somersetshire - 400, etc.). M. were created in metalworking. Birmingham industry is booming. industry (Spilman and Churchard enterprises in Buckinghamshire), in glassmaking (Munsel's large enterprise). After the revolution, the unhindered development of M. proceeded even more successfully. In the Netherlands, M. spread in the 16th century. everywhere, especially in new industries and new industries. centers not associated with shop restrictions. On the basis of the village industry in Flanders, wool weaving mills developed early (for example. , in Hondschot), carpet m. around Oudenaarde with a scattered system of home production; Antwerp was famous for its soap and sugar refineries, large workshops for finishing English. cloth, the largest printing house of the Plantens. Means. M. became widespread in the text. production (M. in Valenciennes, Mons, in the region of Liege), in oil production, brewing, soap making, shipbuilding, in rope and sail production. M. developed extremely quickly in the 17th century. (after the victory of the bourgeois revolution) in Goll. republic. In France 16-17 centuries. The basis for the development of dispersed manufacturing was the village cloth, leather, and other industries, which flourished most around the cities. Centralized ministries in cities were small in size (in book printing and metalworking). Mixed fabrics were more common (for example, silk Lyonnaise fabrics). The so-called "royal manufactories", representing significant enterprises under the tutelage of the queens. authorities. A characteristic feature of the French M. - production of luxury goods: velvet, satin, lace, etc. On the eve of the Burzh. revolution con. 18th century M. developed into wool. and cotton-boom. industry of cities and villages of the North. France; large, although few in number. enterprises were created in metallurgy and other industries. In Spain, it barely began to develop in all industries in the 15-16th centuries. M. withered away as a result of the general economic. the decline of the country in the 17th century; some economical rise in the 18th century manifested itself in the development of fabrics (text fabrics in Catalonia, cloth, silk weaving, and paper fabrics in Galicia and Basque Country). In the 2nd half. 18th century M. is flourishing again in Italy (scattered and centralized M. in Lombardy, Piedmont, etc.). On the territory Germany (and Austria) M. developed from the end of the 15th and 16th centuries, however, under conditions of general economic. decline and M. died out. Some revival of M. is planned in Germany. state government since the end of the 17th century. In Württemberg, Thuringia, Westphalia, and Silesia, peasant home crafts (spinners, weavers of wool and linen fabrics, etc.) were widely developed. Here, as a rule, mixed buildings arose. They were also created in the cities of Brandenburg: foreign. colonists (French Huguenots) founded wool, paper, etc. here. However, the general economic. backwardness of Germany in the 17th and 18th centuries. gave these M. a stagnant character, characteristic of the country's industry until the beginning. 19th century Being in the 16th-18th centuries. the dominant form of industrial organization, M., however, “... was not able to either embrace social production in its entirety, or transform it to the very root. It stood out as an architectural decoration on an economic building, the broad basis of which was the urban craft and rural side trades" (Marx K. , Capital, vol. 1, p. 376). At the same time, M. deepened and expanded social and technical. division of labor, created for the first time large-scale production and capacious internal. market, thereby preparing the transition to a new, factory stage of capitalism, which came as a result of the industrial revolution. Complexity concrete-ist. development of M. caused among owls. historians have had a number of discussions. Thus, the subject of discussion was the question of the nature of early manufacturing, in particular in Italy (see collection of Middle Ages, v. 4, 1953, v. 5, 1954, v. 6, 1955), the question of the nature of M . in Russia (a study of the history of Russia and certain other countries showed the existence of forms of industry similar to M. in production and technical structure, but based on the exploitation of forced labor). Many controversial, complex and unexplored problems are associated with the emergence and spread of M. in the countries of the East. In general, small-scale production in these countries in the context of deepening societies. The division of labor and the growth of its productivity could not but show capitalism. trends; in a number of countries, on the basis of small-scale commodity production, capitalist production arose (along with other initial forms of capitalist production). M. In different countries of the East, it was at different stages of maturity both in relation to the organization of production and in relation to the degree of participation in the national. system of societies. division of labor. M. received relatively distinct forms in Japan and China, where early capitalist. relations originate in the 16th-18th centuries. (however, as researchers emphasize, for the period of the 16th-17th centuries, information about the existence of M. is still random, only separate institutions are mentioned). M. were available, for example, in text., metallurgy., shipbuilding. industry, sugar making and tea processing. In addition to private mills, state-owned ones were also common, based on the labor of dependent peasants (mainly in porcelain production and silk weaving). Similar phenomena were noted at a somewhat later time in Vietnam (in shipbuilding, weapons manufacturing, etc.). In the 2nd half of the 18th century. to the ironworks. production in Mysore (India) there were enterprises that had certain characteristics of M. Initial forms of capitalist. production organizations and, in particular, sporadic. the emergence of M. can also be noted for some Arabs. countries con. 18 - beginning 19th centuries However, most countries of the East never passed through the manufacturing stage of capitalism. Capitalist trends development - due to general unfavorable economic conditions. and political conditions - turned out to be in. parts unsold; involvement of most Eastern countries in the colony. and semi-colon. addiction has changed nature. their progress is economical. development. The emergence of large-scale industry in these countries in the subsequent history. period is already associated with other, higher forms of capitalism. production However, they did not always arise without any connection with the development of local manufacturing. The appearance of the department manufacturing industries and factory production in a number of cases was associated with the evolution of local manufacturing (as a rule, in those industries that did not compete with the industry of the metropolis). Lit.: Marx K., Capital, vol. 1, (M.), 1952, ch. 11-12, 24; vol. 3, (M.), 1955, ch. 20; Lenin V.I., Handicraft census of 1894/95 in the Perm province and general issues of the “handicraft” industry, Works, 4th ed., vol. 2; him, Development of capitalism in Russia, ibid., vol. 3; Genesis of capitalism in industry, M., 1963; The genesis of capitalism in industry and agriculture. x-ve, M., 1965; Kovalevsky M. M., Economic growth of Europe before the emergence of a capitalist economy, vol. 2-3, M., 1900-03; Kulisher I.M., Industry and the working class in the West in the XVI-XVIII centuries, St. Petersburg, 1911; Sombart W., Modern capitalism, trans. from German, vol. 1-2, M., 1903-05; Strieder J., Studien zur Geschichte kapitalistischer Organisationsformen, M?nch., 1925; Hauser H., Les d'buts du capitalisme moderne, P., 1926; S?e H., Les origines du capitalisme, P., 1927; Nef J. U., Industrial Europe at the time of the Reformation, "The Journal of Political Economy", 1941, v. 49, No. 1-2; Dobb M. H., Studies in the development of capitalism, L., 1946. Rutenburg V. I., Essay on the history of early capitalism in Italy..., M.-L., 1951; Chistozvonov A. N., Investigate phenomena in their history. identity and connections, in collection: Wed. century, century 6, M., 1955; Meshcheryakova N. M., About the industry. development of England on the eve of the bourgeoisie. revolution of the 17th century, ibid., c. 7, M., 1955; Ashley W. Y., The economic organization of England..., (2 ed.), L.-N. Y., 1935; Lipson E., The economic history of England, v. 2-3, L., 1948; Lyulinskaya A.D., On some features of the manufacturing stage in the development of capitalism (using the example of the Fraction in the early 17th century), in: Wed. century, century 27, M., 1965; Sidorova N.A., Village industry of Champagne on the eve of the revolution of 1789, "Uch. Zap. MGPI", 1941, vol. 3, century. 1; Martin G., La grande industrie sous le r?gne de Louis XIV..., P., 1899; his, La grande industrie en France sous le r?gne de Louis XV, P., 1900; Cole Ch. W., Colbert and a century of French mercantilism, v. 1-2, N.Y., 1939; Kr?ger H., Zur Geschichte der Manufakturen und der Manufakturarbeiter in Preussen, V. , 1958; Bicanic R., Doba manufakture u Hrvatskoj i Slavoniji (1750-1860), Zagreb, 1951; India. Essays on economics. history, M., 1958; On the genesis of capitalism in the countries of the East (XV-XIX centuries), M., 1962. N. M. Meshcheryakova, L. S. Gamayunov (M. in the countries of the East). Moscow. Manufactory in Russia. Ch. feature of M. in Russia 17th - 1st half. 19th centuries was that they were formed and grew under the domination of feudal serfs. relations in the country. At 17 - beginning. 18th centuries The prerequisites for the emergence of metallurgy in those branches of industry were ripe, the products of which were widely sold internally. and ext. markets (salt making, distilling, production of yufti, etc.). In these industries, capital, organizing capital, united the labor of hired workers in relatively few specialties. In the salt-making industry of the 17th century. there were approx. 10 M., in a tannery in the 20s. 18th century More than 30 companies produced yuft for export, and even more were produced in the distillery industry. At 17 - 1st Thursday. 18th centuries in these industries there was the largest number of companies with a predominance of capitalist ones. relationships. The majority of M. in 17 - 1st quarter. 18th centuries arose with the active assistance of the state in those industries in which the conditions for their emergence were not yet ripe. In addition to the construction of state-owned buildings, production already in the 17th century. provided privileges to private entrepreneurs, and by the 20s. 18th century A whole system has been developed to encourage entrepreneurship in industries needed by the state (financial subsidies, transfer of goods created by the treasury into the hands of private owners, provision of labor force for small ones and assigning it to them, purchase of all or a significant part of products by the treasury, etc. .). In the 17th century with the assistance of the production company M., chapters were created. arr. in metallurgy (factories of A. Vinius, P. Marcelis - F. Akema, etc.). In the 1st quarter 18th century 178 such M. have already appeared (89 government-owned and 89 private). In total, by 1725 in Russia there were approx. 200 M., subordinate to the Berg and Manufactory Collegiums, or the so-called. “decreed” (55 metallurgical and weapons factories, 15 cloth factories, 9 sail-linen factories, 13 leather factories, etc.), providing for the army, navy, and the needs of the state apparatus. “Ukaznye” M. were distinguished by a complex division of labor within the enterprise, often cooperating with hundreds of workers of many specialties. Means. Some workers, especially in the light industry, came to such M. themselves. Metallurgical enterprises were almost entirely serviced by force. labor of assigned peasants and other workers. The government also assigned peasants to private (ownership or possession) farms, and in 1721 allowed the owners of farms to purchase peasants. In general, for socio-economic M.'s "decreed" system was characterized by a combination of serfdom. and capitalistic elements, and in state-owned factories (see also State-owned factories) and most private factories, serfdom had a predominant role. relationship. Their dominance became widespread in the “decreed” M. in the 30s and 40s. 18th century, after the production in 1736 permanently assigned workers to enterprises (possession workers). Serfdom relations also prevailed in patrimonial industries (see Patrimonial industry). Development of M. Russia in the 2nd half. 18 - 1st third of the 19th centuries. was characterized by an increase in the number of M., especially capitalist ones, the number of workers, and the growth of capitalist. elements in the "index" M., ch. arr. in the light industry, the beginning of the M. crisis, main. on force. labor Number of capitalist M. not taken into account. According to N.L. Rubinshtein’s calculations, they were employed in small establishments and spinning work in the 60s. 18th century 45 thousand, in con. 18th century - already 110 thousand civilian workers, mainly. peasant otkhodniks. Of the thousands of small establishments, relatively few M. stood out here, which means they concentrated. part of the employees and products: in 1789 out of 226 establishments with 633 employees. There were only 7 (3.1%) Ivanovo M., and there were 245 workers (about 40%). Absent-mindedness has developed, especially in text. prom-sti. The number of enterprises subordinate to the Manufacture Collegium, and later to the Department of Manufactures, grew rapidly (from 496 in 1767 to 2094 in 1799, etc.). Share of free-hire. workers increased by 1767 to 39.2%, by 1804 to 47.9% and by 1825 to 54.4%. Most of all enterprises, incl. M., it was in the text. prom-sti. Based on capitalist growth. At this time, the agricultural boom was rapidly developing. industry The number of workers in it increased from 1.9 t.h. in 1799 to 90.5 t.h. in 1835, and more than 90% of them were civilian employees. Capitalist M. began to predominate in the silk and sailing-linen industries. M. remained important in the cloth industry, producing ch. arr. cloth for the army. Possessional and especially patrimonial businesses predominated here. The number of workers on them grew predominantly. at the expense of patrimonial serfs. From 30.6% (11.1 t.c.) in 1799, their share rose by 1825 to 60.6% (38.5 t.c.), while the share of sessional workers fell from 53.6% ( 19.4 t.p.) to 20.9% (13.3 t.p.). A serf citadel. relations remained with the mining industry. At the turn of the 18th-19th centuries. in Russia there were approx. 190 mountain plants. They were served by 44.6 thousand serf artisans and 27-28 thousand civilian workers. Auxiliary the work was carried out by assigned peasants (319 t.ch. ). Basic a lot of mining enterprises were concentrated in the Urals. Since the 30s. 19th century M. developed under the conditions of the beginning of the industrial revolution in Russia. In 1835-60 a factory cotton boom developed. spinning, the factory began to play a predominant role in the calico printing industry and in the stationery industry, weaving factories appeared and the number of weaving machines grew, the transition to a factory began in the beet-sugar industry and certain other industries. In this regard, in a number of industries (calico printing, stationery) the growth stops, and then the number of mills begins to decline. The revolution is associated with the emergence of manufacturing with the steam engine and the transformation of manufacturing of a number of industries into an appendage of the industry (cotton and paper weaving, etc.). However, in most branches of industry in 1835-60 the number of M. continued to grow - predominantly. at the expense of capitalist M. By 1860, civilian workers were being processed. industry was approx. 80% of the total number of workers. Civilian workers began to predominate even in such industries as the woolen (cloth) industry, which was associated with the growth in the number of factories, rather than mills, that produced fine and semi-fine wool. fabrics for interior market and export them to Asian countries. As a result, the share of civilian workers here increased to 58%, while other categories of workers decreased: patrimonial from 60.6% to 34%, sessional from 20.9% to 8%. In ferrous and non-ferrous metallurgy it will be forced. labor continued to be the main thing. form of labor organization. Completion of industrial The coup in Russia occurred after the cross. reforms of 1861. At this time, the use of coercion disappeared. labor in industry, incl. and on M. So. some of the factories grew into factories, and the surviving factories became a secondary form of industrial organization. In the 2nd half. 19 - beginning 20th centuries M. existed in plural. industries as an appendage of a factory or as a form of organization of production brought to life by a factory (for example, weaving matting, preparing paper boxes for packaging, etc.). But in Russia, centralized and scattered microorganisms that did not have direct influence continued to exist. connections with factory production. They remained the highest form of capitalist organization. production in industries for which a system of machines has not yet been created (fulling, furriery, production of locks, samovars, accordions, etc.). In a huge and diverse country with a diverse structure. M.'s economy remained independent. meaning in plural backward and outlying districts. They disappeared only after Oct.'s victory. revolution. Data about M. was collected and described back in the 18th century. (I.K. Kirilov, V.I. Gennin, M.D. Chulkov and others. ). But at this time and in the 19th century. historians did not single out manufactories. production as a special form in industry and a special stage of its development. In the 2nd half. 19th century There was a division of Russian industry into factory industry, which included any large centralized production, incl. and centralized M., and artisanal. At the same time, researchers who shared populist views on the fate of capitalism in Russia tried to prove non-capitalist. the nature of the artisanal, “folk” industry, contrasting it with the large, capitalist one. prom-sti. The latter, starting with the enterprises that arose under Peter I, considered it artificially created, which did not have the conditions for its development in Russia. Their opponents (G.V. Plekhanov, M.I. Tugan-Baranovsky and others) argued for capitalism. nature of the handicraft industry 2nd floor. 19th century and its connection with the factory industry (M.I. Tugan-Baranovsky, Russian factory in the past and present, vol. 1 - Historical development of the Russian factory in the 19th century, St. Petersburg, 1898, 7th ed., M. , 1938). Valuable material on the development of M. into a factory is contained in the study of E. M. Dementyev (“The Factory, What It Gives to the Population and What It Takes from It,” M., 1893). But accumulating valuable facts. material on the development of metallurgy in Russia, bourgeois. historiography continued to confuse mass media with other forms of large-scale industry and concentrated attention on solving the problem posed by the populists. historiography - whether large enterprises in Russia in the 18th and 19th centuries were artificially created organisms or not. V.I. Lenin was the first researcher to identify manufactories. stage of Russian industry and showed the features of the development of M. in pre-reforms. and after the reforms. period. He established a criterion for distinguishing metals from various types of handicrafts and also studied the development of metals in various branches of the country's industry using materials from the 2nd half. 19th century (see "The Development of Capitalism in Russia", Works, vol. 3). Sov. historiography develops Lenin’s concept of the origin and development of history in Russia. Sov. historians have proven the existence of socio-economic. conditions for the emergence and development of metallurgy in Russia since the 17th century, the history of metallurgy has been deeply studied, incl. features of its development in metallurgy (Yu. I. Gessen, D. A. Kashintsev, S. G. Strumilin, B. B. Kafengauz, N. I. Pavlenko, etc.), in the light industry (D. S. Baburin, E.I. Zaozerskaya, etc.), the development of the manufacturing industry in the end. 18 - 1st floor. 19th centuries (P. G. Ryndzyunsky, V. K. Yatsunsky, etc.). Since the 30s. in Sov. historiography there is a discussion about socio-economic. nature of M. Russia, especially 17-18 centuries. Part of it was the publication of discussion articles in journals. “Questions of History” in 1946-47, 1951-52 (articles by N. L. Rubinstein, Zaozerskaya, Strumilin, etc.). Some researchers consider M. to approximately mid. 18th century and that means. Some of the capitals of subsequent times were serfdom (M.F. Zlotnikov, M.P. Vyatkin, Rubinshtein, etc.), others, especially Strumilin, were capitalist from the moment of the appearance of capitalism in Russia. In the 50s a third point of view has taken shape, towards which the present day tends. time, most historians and economists: serfs stand out. patrimonial M.; the rest of M., which arose in the 17th - 1st half. 18th centuries with the participation or active assistance of the feudal serfs. states are characterized by varying degrees of combination of serfdom. and capitalistic traits with a predominance of the former, especially in metallurgy; in the subsequent period (until 1861) the emergence and development of capitalism took place. M., and in sessional M. the specified combination is preserved with the growth of capitalism. hell, slow in metallurgy, in cloth, stationery and other industries and much faster in silk, linen, etc. Research in recent years (N.V. Ustyugov, Salt production industry of Kama Salt in the 17th century. On the question of the genesis of capitalist . relations in Russian industry, M., 1957, etc.) allow us to clarify the considered point of view, adding that in certain industries of Russia, most closely related to internal. and ext. markets, capitalistic M. began to appear in the 17th century. Among the owls Historians also have discrepancies in the dating of the beginning of manufactories. period in the development of Russian prom-sti. Most people classify this line as the 2nd gender. 18th century (N.L. Rubinstein by the middle of the century, others - by the 60s, 70s, or even by the very end of the 18th century). Research of the manufacturing industry, publ. at 50 - early 60s, allow, in our opinion, to attribute this facet to an earlier period, approximately at the end. 17th century Lit. see under art. Capitalism in Russia. M. Ya. Volkov. Moscow.